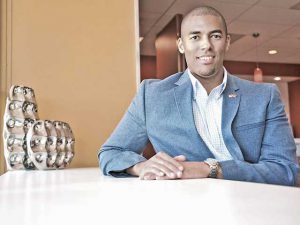

U.S. Marine combat veteran Joshua Rivers says a marine isn’t thinking about the American flag, apple pie, or even their mother when bullets are flying overhead. They think instead about the man or woman next to them, the one they’ve lived with, drank with, played with for the previous one, two, or 10 years.

U.S. Marine combat veteran Joshua Rivers says a marine isn’t thinking about the American flag, apple pie, or even their mother when bullets are flying overhead. They think instead about the man or woman next to them, the one they’ve lived with, drank with, played with for the previous one, two, or 10 years.

Rivers, a Saugus resident, served with Kenny Bass for less than three years, ending in 2003.

But the two now fight a different battle.

Together they’ve taken up the cause of veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder by pairing them with service dogs trained to help ease their symptoms, and by striving to promote a higher quality of life for disabled veterans.

Sparked by friendship

Rivers and Bass met roughly seven months before Sept. 11, 2001, when Bass came to Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton near San Diego as one of Rivers’ junior Marines.

“We hit it off really well,” said Bass, who was a groomsman in Rivers’ wedding. “We were both from Ohio, (and) from the beginning I liked the guy. He’s very up front and forward. You don’t have to guess what he’s thinking (because) he has probably already told you.”

The men traversed the ocean in 2003 when their platoon invaded Iraq. Rivers was honorably discharged in August of that year, Bass in Sept. 2004.

“When you get out (of the service) some … were more fortunate and were able to find (the) way back to the civilian world easier than others,” Rivers said, “Our responsibility as veterans is to help those that need that help.”

Bass was one of the less fortunate. He had been wounded, in July 2003, by an improvised explosive device during a counter-ambush patrol. And the mental and physical effects of his service oversees manifested quickly, Rivers says of Bass who has suffered from PTSD, Behcet’s Disease (an autoimmune disease), and multiple other physical injuries.

“It was very difficult for me to see him struggle,” Rivers said, “and even more difficult because there was nothing I could do.”

However, in 2012, Bass texted Rivers asking him to spread word that he’d been prescribed a service dog and was raising money to pay for it: Rivers remained helpless no longer.

A Veterans Affairs’ doctor prescribed the dog to help Bass cope with PTSD symptoms, which, according to the National Center for PTSD, fall into four categories: reliving the traumatic event, negative change in beliefs or feelings, avoiding situations that remind them of the event and hyper-arousal, all of which Bass has experienced.

But although he’s 100 percent service-connected disabled, Bass had to pay for the $15,000 canine on his own because, citing lack of research supporting a positive correlation between service dogs and PTSD-patient recovery, the VA didn’t cover it. He eventually found an organization that allowed him to make payments, he says.

As Bass explained to Riverswhat his German Shepherd, Atlas, did and how it was helping him, a light bulb went off.

“Very, very early in (our) conversation…I could tell how this dog was helping him,” Rivers said. “It was very easy to see glimpses of the old guy I knew, pre 9/11, coming through in his overalldemeanor…(he was) just more relaxed.

“I said, ‘let’s start a charity and help other veterans get service dogs.’”

In early 2013, the men started The Battle Buddy Foundation, which received national exposure through a Facebook page (now with over 192,000 likes) created by Bass and his brother Jon Campbell, TBBF’s third co-founder.

The Ohio-based non-profit placed its first dogs later that year, and by 2013’s end, TBBF’s momentum was a bit overwhelming, Rivers said.

Rivers, who works out of TBBF’s Valencia branch which opened in February, says around 4,000 veterans or their spouses have contacted the foundation about service dogs since its inception, and hundreds more are looking for employment within TBBF.

The program

TBBF’s long-term goals focus on helping veterans and their families through veteran employment and mentorship programs, as well as working with legislators and promoting research for PTSD, Traumatic Brain Injury and veteran suicide (a VA report says 22 veterans commit suicide every day).

But where “the rubber hits the road,” Rivers said, is TBBF’s service dog program.

The program pairs veterans suffering from PTSD or facing mobility limitations with psychiatric and mobility service dogs in an attempt to mitigate their disabilities.

Unlike similar foundations, TBBF has the veteran go through training with the dog, an 8-12 month process, in order to give them a new sense of mission and responsibility.

During training, the dogs learn tasks specific to their veteran’s needs like waking them from nightmares, reminding them to take medications, and sitting so as to face behind their back (easing anxiety that someone could sneak up from behind).

Rivers acknowledges that service dogs aren’t the cure-all for the disorder. The program, he said, is only a part of a veteran’s recovery.

Nevertheless, TBBF’s aim is to play that part by seeking to place 150-300 dogs each year at no cost to the veteran.

To date, they’ve placed seven dogs.

Reasons for the low placement number, Rivers said, are the dogs’ high washout rate, the foundation’s small volunteer staff, and the large amount of time it takes to train the dogs.

The main restricting factor, however, remains the lack of funding that keeps at least six dogs and veterans from starting the program, and bars TBBF from training and hiring an additional six veterans as trainers.

TBBF currently employs three trainers and holds three weekly meetings in the Cincinnati area for the placed dogs and their veterans (all seven live in Ohio and Indiana).

Rivers said he’s aware of a large population of veterans in the Santa Clarita Valley (10,000 veterans according to an estimate from SCV Veterans Memorial Inc. President, Duane Harte) and would like to start placing dogs locally.

But for the 34-year-old, his fight isn’t only for the SCV, or for Bass, or even for current veterans across the country; he said, in the same up-front manner that endeared him to Bass, it’s a fight for future veterans.

“How can I, as a U.S. Marine combat veteran, look a high-school student in the eye and tell them I think it’s advisable to join the United States Military when promises are being broken right now that were made to our veterans five, 10, 15 years ago,” Rivers said. “That’s what we have to fix. That’s what we’re fighting for.”

Written By: Mason Nesbitt

Source: The Santa Clarita Valley Signal